It’s true, you’ll find many problems in a Haitian orphanage. But you will also find some cures.

One is the cure for self-pity. No matter how uncomfortable you are in the States, they’re more uncomfortable in Haiti. No matter how broke you are in America, they’re more broke in Haiti.

And no matter what you have to endure, there are children in Haiti who have endured more.

Two of them live with us.

Their names are Knox and Gaelson. They both recently turned 10 years old. Given their backstories, that alone is a bit of a miracle.

Let’s start with Knox. The kid is liquid sunshine. A blinding smile. Wide-eyed enthusiasm. An endless stream of happy conversation. And I have almost never seen him cry.

Not that he lacks reason. Abandoned when he was an infant, in a patch of woods behind a hospital, he was taken in by a passing woman who found him and tried to raise him. When Knox was one year old, he either fell or leapt from a table top and smashed his head open. The doctors had to perform emergency brain surgery.

That procedure left Knox akin to a stroke victim. His left arm was locked and raised nearly to his clavicle. His left leg was permanently bent, his foot only touching the ground at its toes. When he was brought to the orphanage, it was nighttime (a strange time to visit) and he was sleeping. When we woke him up to talk to him, he initially refused to speak. He was only three years old; he must have been petrified.

Finally, our wonderful American school director at the time, Anachemy MIddleton, had a brilliant idea. She sat behind him, wearing two hand puppets, and let the puppets talk to him instead.

He lit up.

And has never stopped shining.

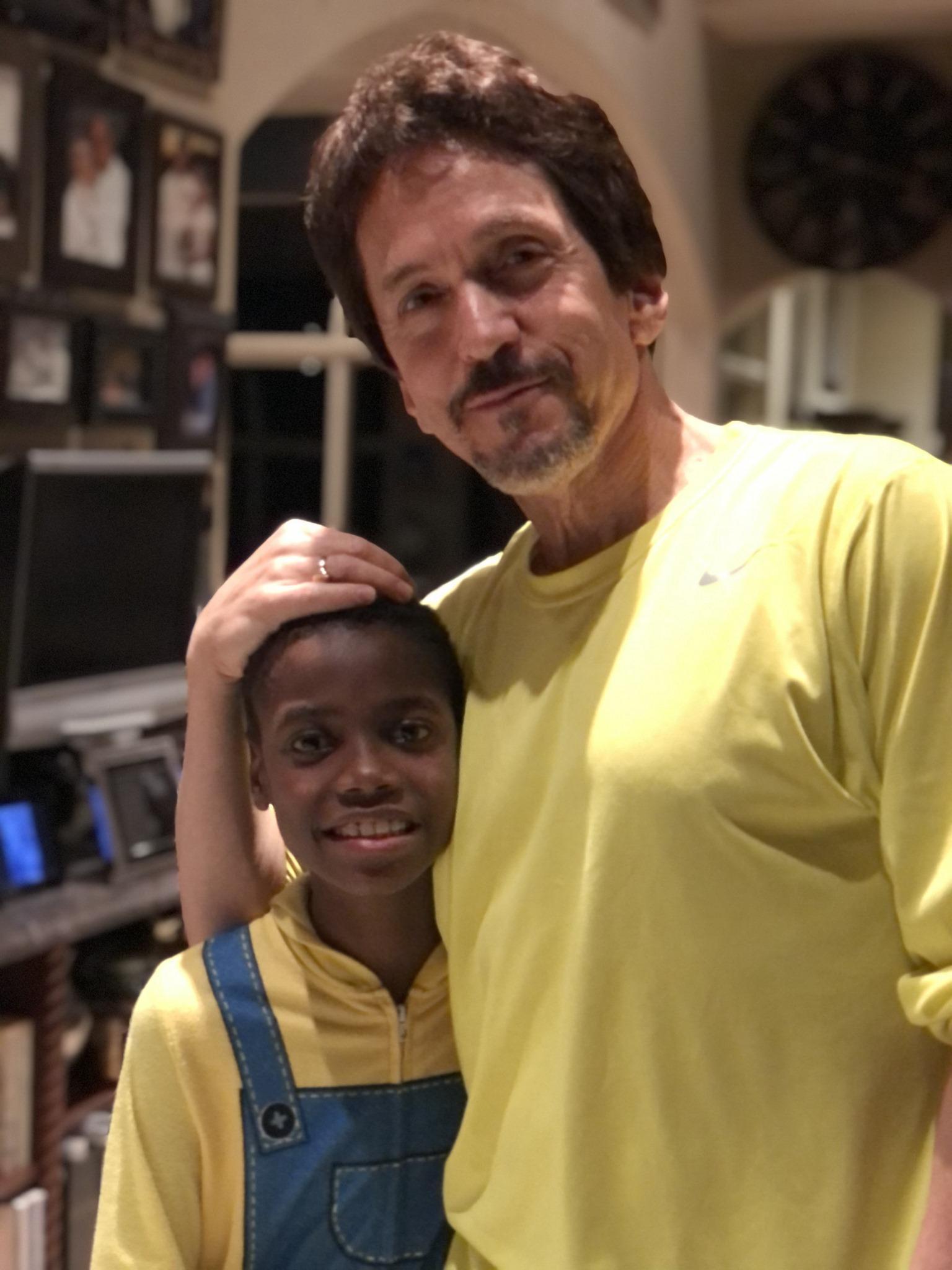

Mitch and Knox / Photo credit: Connie Vallee |

The six million dollar boy

Knox has been coming to America for medical treatments for nearly four years now. A brilliant doctor named Edward Dabrowski devised a plan of injections and rehab. And a team at Beaumont Hospital Physical Therapy puts Knox through grueling routines of stretching, stimulation, even an avatar-like machine that he slips inside; it allows him to see an animated version of himself on the screen as he manipulates walking.

These medical and therapy experts donate their time and services partly because they are just good, caring people — and partly because he is Knox. All the kid does is smile. He jumps in to every activity. And he never stops talking.

“Oooh!” he will say, pointing at a cartoon character, “that is from Sonic the Hedgehog, not true?”

(Knox says “not true” at the end of sentences because in Creole, the phrase “pas vray?” is used the same way. So he will say “We’re having pizza tonight, not true?” And we will answer, “True.”)

Knox will point things out through the window. He will ponder the universe. He will ask who will win a race, “Superman or the Flash?” and then make the case for each one. Despite his limitations, he never sees a half-empty glass.

How he does this so cheerily, while limping through activities, holding everything one-handed, turning the pages of a book with his good fingers while keeping it down with an elbow — well, I don’t know.

But it is inspiring.

Mitch and Gaelson / Photo credit: Connie Vallee |

The boy who lived

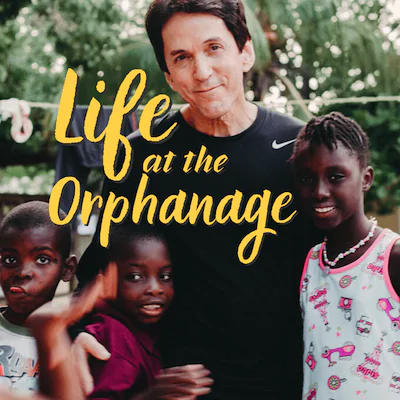

The same goes for Gaelson. His backstory parallel’s Knox’s. When he was very young, someone in the provinces brought him to a tuberculosis clinic, because he had been coughing.

They never came back for him.

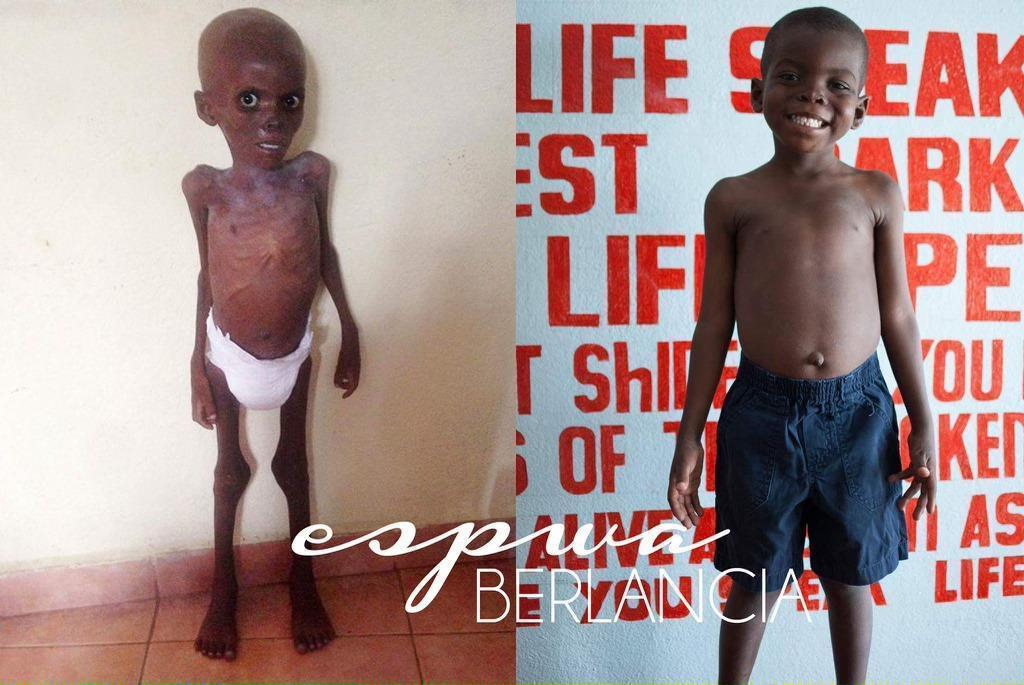

He lived there for more than a year, despite the fact that he did NOT have tuberculosis. Then, having withered to a shocking, skeletal weight, he was taken to a malnutrition center. Again, there was no one to claim him. He stayed there for a long time, until they could no longer be responsible for his daily care. They contacted us at the Have Faith Haiti Orphanage, and we took him in.

Tracking Gaelson’s progress at the malnutrition clinic. |

Where Knox was garrulous, Gaelson was silent. Getting him to say anything was a big deal. But when he did speak, his squeak of a voice revealed a child seeking love and attention in the most desperate, moving way.

Gaelson coughed constantly. We were repeatedly told it was nothing. Then, a few years ago, he stopped eating. Anything he ate he threw up. We rushed him to a series of Haitian doctors, none of whom could do anything for him. It turned out he had a hole in his esophagus, so anything he ate or drank was going into his lungs. This could cause aspiration and if not addressed, death.

No one in Haiti could address it.

In the dead of winter, we managed to get him out of Haiti and to Detroit, where an incredible team of doctors and nurses at Children’s Hospital in Detroit, led by a surgeon named Justin Klein, operated multiple times on Gaelson, eventually closing the hole and removing a withered lung which wasn’t functioning.

Gaelson was in the hospital for more than a month. At times the pain was excruciating. But he held that stoic posture. He gripped a stuffed animal (a hedgehog) and let his tears fall silently. He endured better than most adults would. And when he came home, that sweet squeak of a voice began to open up, to ask for something to eat, for a Lego set to play with, to say “I love you.”

Bonded as a team

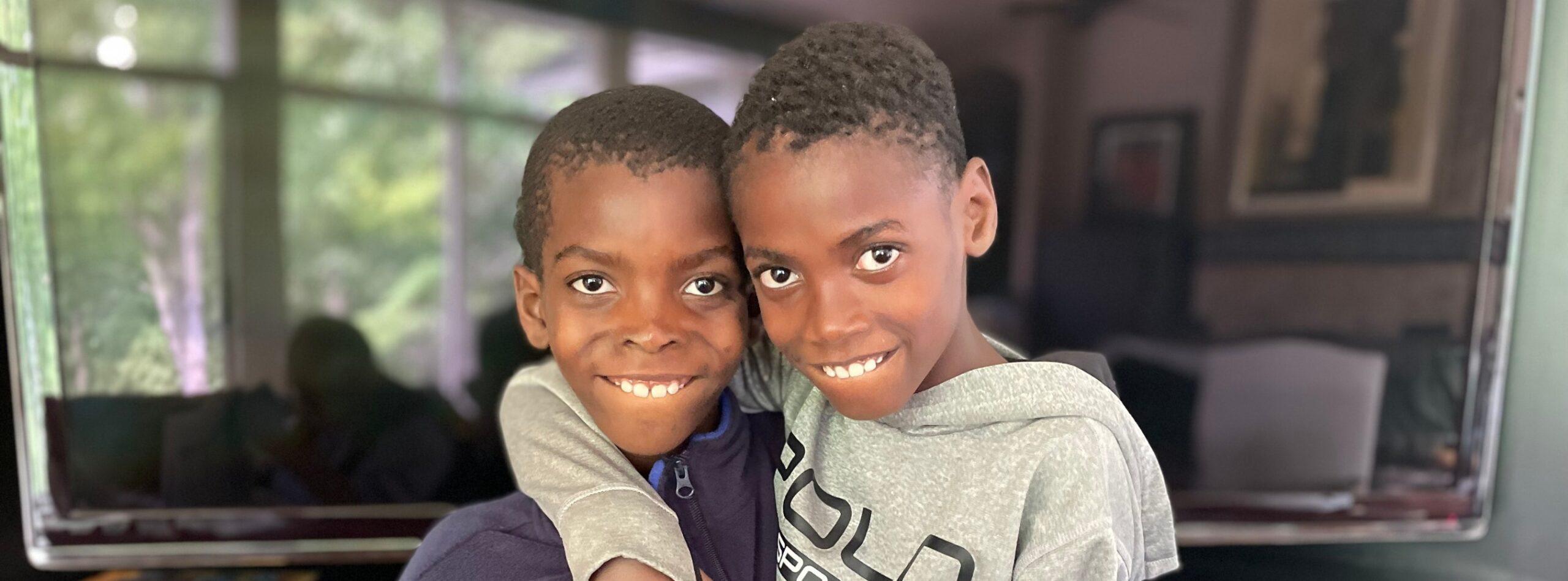

Recently, Knox and Gaelson came for medical treatments at the same time. This was during the start of the pandemic, and suddenly, while they were here, getting back to Haiti became difficult. So they stayed in the U.S. for several months, sharing a single bedroom, and we got to watch a small miracle: perhaps sensing their shared medical challenges, or the fact that they began life shunned by those who should have loved them, Knox and Gaelson became a team. They grew inseparable. They watched Lilo and Stitch cartoons while lying on top of each other. They shared toy trucks and action figures. They giggled and whispered before going to bed. And they weren’t the least but self-conscious about hugging each other for photos.

Knox and Gaelson in Michigan / Photo credit: Connie Vallee |

What they didn’t do is complain. Never. We never heard “I don’t WANNA go!” We never saw a refusal to put on a jacket when heading to the hospital, or a pouting attitude when a doctor’s appointment loomed. They seem to get, as all our kids seem to get, that being helped should be met with gratitude, not complaint. They hug the doctors and nurses who tend to them. They draw them pictures.

There’s a famous play (and movie) written by Neil Simon called “The Sunshine Boys.” It’s about two old comedians who are constantly feuding.

We’ve got the real Sunshine Boys. They’re 10 years old. And whenever I am feeling sorry for myself, I look at them in our yard, Knox running with that one good foot, Gaelson riding a bicycle with his one good lung, and I realize I have one good existence, and very little to complain about.

That’s also part of life at the orphanage, where we are occasionally plagued by sickness, but continually surrounded by cures.

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments