👋 and welcome to “Life at the Orphanage,” a newsletter about life for the 50+ children of Have Faith Haiti. Follow along as I share the universal lessons learned watching the purest of childhoods in one of the poorest places on earth. Looking forward to hearing what you think in the comments.

PORT-AU-PRINCE — When you first arrive at our orphanage, the kids will descend like bees. They’ll buzz you and hug you and study your clothes and pull at your hair, especially if it is substantial. Then, amidst their giddiness, they’ll ask you a question:

“How long will you stay?”

It is more than curiosity. It is defense. Orphaned kids have many fears, but the worst is abandonment. They have all been left behind at least once in their lives. Most are afraid it will happen again.

So when new people come in, the kids measure their intended stays, then subliminally dole out the affection they’re willing to risk. A long stay means unbridled love. A short stay means they’re more guarded. Deep down, the kids sense a price for getting attached. They still want that attachment. But they are scared of being ditched.

This is one reason I come here every month, without fail, and have since 2010 (except for four awful months at the start of COVID-19.) When the kids get sad upon my departure, they’ll ask, “When are you coming back, Mr. Mitch?”

“What month is it?” I always say.

“March.”

“What month comes after March?”

“April.”

“So that’s when I’ll be back, right?”

It seems to work. Knowing there is a reliable return, one that they can point to on a calendar, eases the pain of saying goodbye. They see it my leaving as an absence, not a farewell.

Farewells, they don’t like.

Farewells break their hearts.

We had a farewell last week.

It broke all of ours.

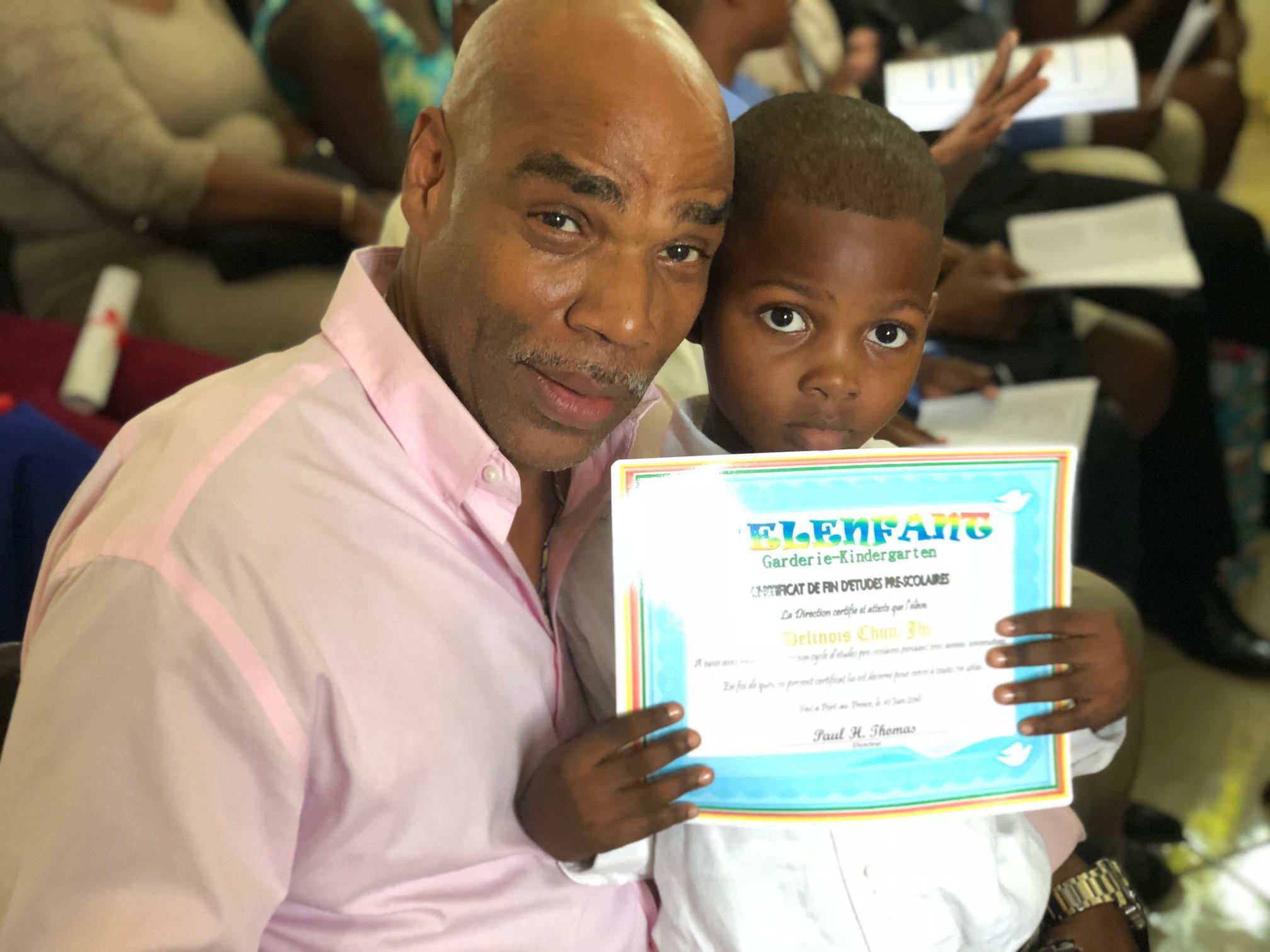

Teacher Phedre (left) with students who completed Collége 1 grade level in the spring of 2019 / Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

Not long enough

Vladamir Delinois was one of our top teachers. He went by the name “Phedre” – or “Mr. Phedre” to our kids. A stocky, smiling man who could look menacing in a helmet and sunglasses yet soft and fatherly with a couple of kids in his lap, Phedre had a radio-announcer’s voice that boomed from one end of the grounds to the other.

We met him during our first few months in Haiti, back in 2010. He stood out because he spoke English like an American. That’s because he left Haiti as a child and lived with his family in Brooklyn, then Florida. He even served in the U.S. Army. When he returned to Haiti, he worked in various security type positions until the 2010 earthquake, when everything stopped.

That’s when we arrived. Phedre knew someone at our orphanage and began to hang around, shooting the breeze with all of us. He was easy to like. He was always telling stories, laughing loudly, earning the nickname “Hollywood” from some of the crew. He had grown children and a new baby son. He loved kids. You could see that. A few years later, when we needed English teachers, he applied, and we welcomed him onto our staff.

Louvenson and Phedre at a recent beach club field trip / Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

During the past few years, Phedre worked tirelessly with our high schoolers on their TOEFL test preparations. The TOEFL (Test Of English as a Foreign Language) is the gold standard for foreigners wishing to study at American universities.

Phedre reveled in getting our kids ready. He was constantly asking me to bring the latest study books to increase their chances. He gave mock tests. He coached our kids on how to actually take the exam, what questions to leave behind, how to budget their time.

The goal was to score higher than a 70, a benchmark for admission to many American universities. Last year when Edney, one of our brightest kids, scored a 96 on his first try, Phedre was as proud as a father watching his son score the winning touchdown.

“I knew he could do it!” Phedre bellowed. After the score was posted, we announced it to our kids. And even as they marveled at the number, some set their minds on surpassing it. They knew the path to doing that went through Mr. Phedre.

He was transforming into a sensei, a wise, guiding force that could unlock the mystery to college education and a trip to America. Our kids couldn’t wait to study with him.

Now, suddenly, they can’t.

Phedre died.

During the pandemic, we have many of our staff members live at the orphanage. It’s the only way we can ensure they aren’t exposed to COVID-19. A few staffers could not do this, like Phedre, because he had children to take care of at home.

Consequently, he came and went, and we had him tested twice a week. It was expensive and time consuming, but we valued his health and his teaching. One day, the test came back positive. Phedre immediately went home and quarantined. He stayed out two weeks. Although he had no real symptoms, he stuck with the protocol and when it was safe, we welcomed him back, relieved in a way, that we didn’t have to worry about him catching it anymore.

That was many months ago.

A few weeks ago, Phedre came to visit. He had bad back pain but seemed OK otherwise. A few days later, he said felt sick and went to an aunt who was a physician. He got worse. Next we knew, he was in a hospital. He texted a friend that he was having trouble breathing and that the people at the hospital said he had COVID-19. He was confused. Didn’t he already have COVID-19? Wasn’t he protected against severe symptoms a second time around?

The next day things got worse. He was moved into the Intensive Care unit.

He texted “I’m scared.”

The next day he was gone.

I got a text from Yonel, our Haitian director. “We lost Mr. Phedre today. I am very sorry.”

Phedre with his son, Jhi / Courtesy of the Delinois family |

There one minute, gone the next

It is the kind of death that happens every day here in Haiti — sudden, jolting, no satisfying explanation. Not having been there in that hospital, we don’t know what Phedre was exposed to, or what precautions were taken. We get no report. No charts. No phone calls.

There are rare pockets of decent health care in Haiti, but for the most part, it is a broken system. Poor people go to hospitals. They get scant attention. Sometimes they come out. Sometimes they do not.

Had he lived in America, Phedre would have been vaccinated. He would be alive. But there is no vaccine in Haiti yet, despite being 700 miles off the Florida coast. Everyone here is rolling the dice.

Phedre was 56. We were stunned at the news. The kids cried. The other staff members cried. He was just at our place, revving his motorcycle, pulling off his helmet, flashing that big smile. How can someone be there one minute and be gone the next?

It is the fear that hovers ominously over all of us, and even more so at an orphanage like ours. I feel so badly for Phedre’s family. For his students. For the kids who will never have him grill them on TOEFL questions and beam brightly when they get the answers right.

The night after Phedre died, I got a call from one of our teenage girls at the orphanage. She had asked to use Yonel’s phone. She said she just wanted to talk to me.

“What’s the matter, sweetheart?” I asked.

“I just want to know,” she said, “that you’re not gonna leave.”

“Leave? Leave where?”

“Leave us.”

I swallowed hard. I knew what she meant. It is the emotion rooted in all our children, and, by extension, all of us as well. How long will you stay? For Mr. Phedre, it was not long enough. Not nearly long enough.

Phedre spent an entire day cooking his top-secret chicken wing recipe for a student-teacher meal in 2019 / Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments