Our oldest kids have been trying to fill out college applications. But not the way I remember doing it decades ago.

There’s no Mom and Dad pouring over the words. No letters of recommendation from family friends. No padding the “extracurricular” with sports teams, chess clubs, and charity trips.

For our kids, it’s them and the application.

Which got me thinking about an application memory of my own.

The forms back when I applied (in the 70s) required you to put down your parents’ occupations. And I realized I didn’t really know what my father did. I knew he went to work each day, knew the name of his firm from company picnics.

But his actual work? His job title? I was clueless. My father did not believe in mixing work with family, and dinner table conversation was never about the office or challenges he was facing. It was always about us kids.

So I had to ask my father “Dad, what do you do?” And he said, “Just put down ‘businessman.’” Which is what I did. Apparently, such vagueness didn’t hurt me. I was admitted to the schools I tried.

But it reminded me that you can learn things through college applications. I was reminded of this again when our six oldest kids wrote their 650 word essays.

The essay question was this:

“The lessons we take from obstacles we encounter can be fundamental to later success. Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience?”

Simple question.

Complex answers.

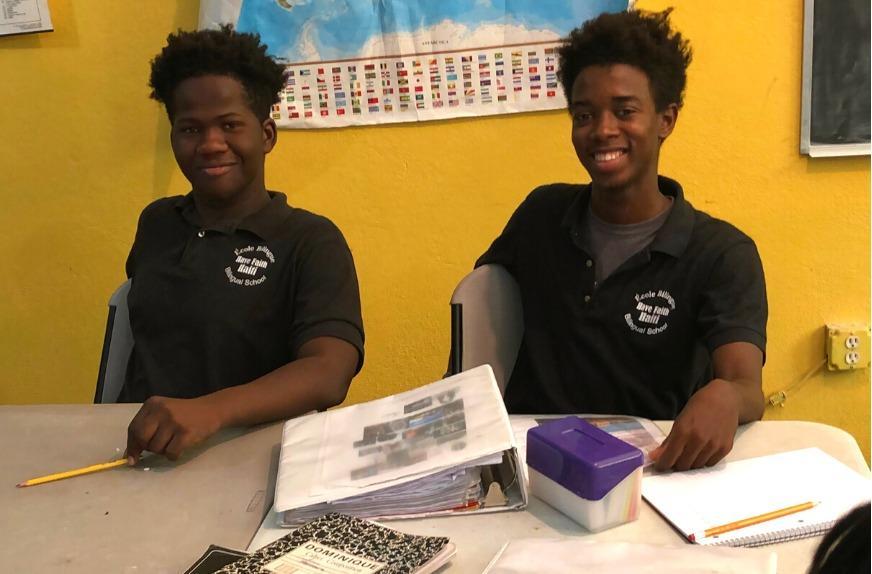

Two Jonathans: left, J.J.; right, J.U. |

In the days before us

As I read the essays, one after another, my eyes teared up. I’m going to share some of them here, but in the interest of respecting privacy, I won’t give any names.

One of our young men wrote:

My house barely had a loaf of bread, never had clean water to drink, and never had sufficient money. I was emaciated with innocent eyes, begging for food in the dirty streets of Haiti. I would walk from town to town, trying to get something that could support the family. Sometimes I was lucky to be handed a coin which I treasured. Other times, I would return home exhausted with empty handed and my father would be ashamed of himself because he had nothing to feed the family. My mother would sing to the hungry children saying that there will be hope and there was no need to cry. I listened to her lullaby, not knowing that I was the hope she was referring to.

I had never heard that story. Because we now take children in so young (age 2 or 3) they don’t really have memories of life before the orphanage.

But I forget sometimes that our older kids arrived when they were 5, 6 even 7. There were days before us. Authority figures before us. Family before us.

In reading the essays, I was shaken to see how difficult those families could be. One teenaged girl wrote:

My dad did not allow bad grades. Unfortunately, I was not a bright student. When I failed at something my father would hit me. Sometimes the neighbors had to come and beg my father to stop.

Another girl began her essay this way:

“I’ll never forget the hot Sunday afternoon that my grandma told me that I was an accident, that my parents were not planning on having me.”

And a young man started his essay with:

“My mother died while giving birth to me. Our family was impoverished, my father was old, my sisters and brothers were young and illiterate. All I could recollect was crying for food and milk. But no one could provide that for me.”

He’s 18 years old now. How long has he been carrying this memory? How long has it burned inside him?

Widley and Kiki |

Stories that move you

As I sifted through these essays, one after the other, I choked up at the thought of how hard life had been for our kids before arriving here. Why hadn’t I been more aware of this? Perhaps because when I conducted the admission interviews, whoever was with the children spoke only of poverty and the inability to offer education or nutrition to the kids. But I never really heard it from the kids’ perspective. And bad adult behavior was rarely admitted.

Then, upon arrival, I guess the group dynamics of 53 children took over. It can overwhelm personal tales of sadness. I imagine, kids being kids, they saw other kids playing and started playing, too. What child would prefer to wallow in sad memories? Not when there is so much new life ahead.

While the essays all included the shattering early years of the kids’ lives, they also included an appreciation for where they are now, which left me humbled and proud. Amongst them:

“Suddenly, God changed my life by leading me to this mission…”

“In the mission mistakes were a normal part of human life, while at my dad’s house I felt like mistakes were a crime…”

“The orphanage taught me to love one another and gave me what I strived for most during my younger years: food, clean water to drink, a proper shelter. I had people taking care of me. I did not have to beg in the streets anymore…”

Reading those conclusions only strengthened my resolve for what we are doing here. And I was once again gobsmacked by the honesty and humble gratitude of the children of Haiti.

I don’t know if our kids will get into all the colleges they apply to. Just getting them to take the TOEFL test is a major undertaking (a risky journey through dangerous streets.) They don’t have Advanced Placement courses. There is no National Honor Society. They lack the means to get a summer job that will boost their resumes.

But they deserve a chance. Reading their essays, you realize their entire lives have been about surviving, enduring, adjusting. I am hoping whoever reviews their applications, they take a real moment to stop and read those 650-word stories.

I’m pretty sure they will be moved. I was.

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments