The graduates formed a long line in the convention center, and the reading of their names began. One by one, they walked across the stage, shaking hands with the university dignitaries, receiving their diploma, waving to cheers.

We sat in a small section of seats near the front, a hodgepodge of family and friends.

“Do you see him?” someone asked.

“Not yet,” someone answered.

“Is that him?”

“Where?”

We craned our necks. We scanned through endless mortar boards. We were trying to spot a certain young man. Not just any young man. Not to us, anyhow.

His name is Emmanuel Gedeon.

He was about to become our first college graduate.

They say there are certain moments parents never forget. A child’s first steps. The first day of school. Taking prom photos on the front porch.

Well, we weren’t there for Emmanuel’s first steps. There weren’t any proms in Haiti. And we are not his parents. But watching him graduate college last Saturday brought out something in my wife and me that I can only liken to a supernova burst of joy and satisfaction.

What a long, strange trip it’s been.

We call him “Manno”

|

Emmanuel — who everyone calls Manno — was already 11 when I came to Haiti and took over the orphanage. He was gentle, polite, and quiet. He read whatever he could get his hands on. We were told his father had died when Manno was young, and his mother had brought him to the orphanage along with his younger brother, Kervens. After a few years, the mother passed away as well. Manno was truly an orphan.

But he was not alone.

Without a secondary school of our own at that point, we paid for Manno to go to a French speaking grade school, and eventually a high school. Every morning he would trudge off in his school uniform, and every afternoon he’d come back to the orphanage. At night he would study outside, under a single light bulb. He often wrote papers in his lap, because there was no desk or tabletop for him to use. I remember reading a report of his once and thinking his penmanship was pretty good if only the pencil didn’t wobble against his thigh.

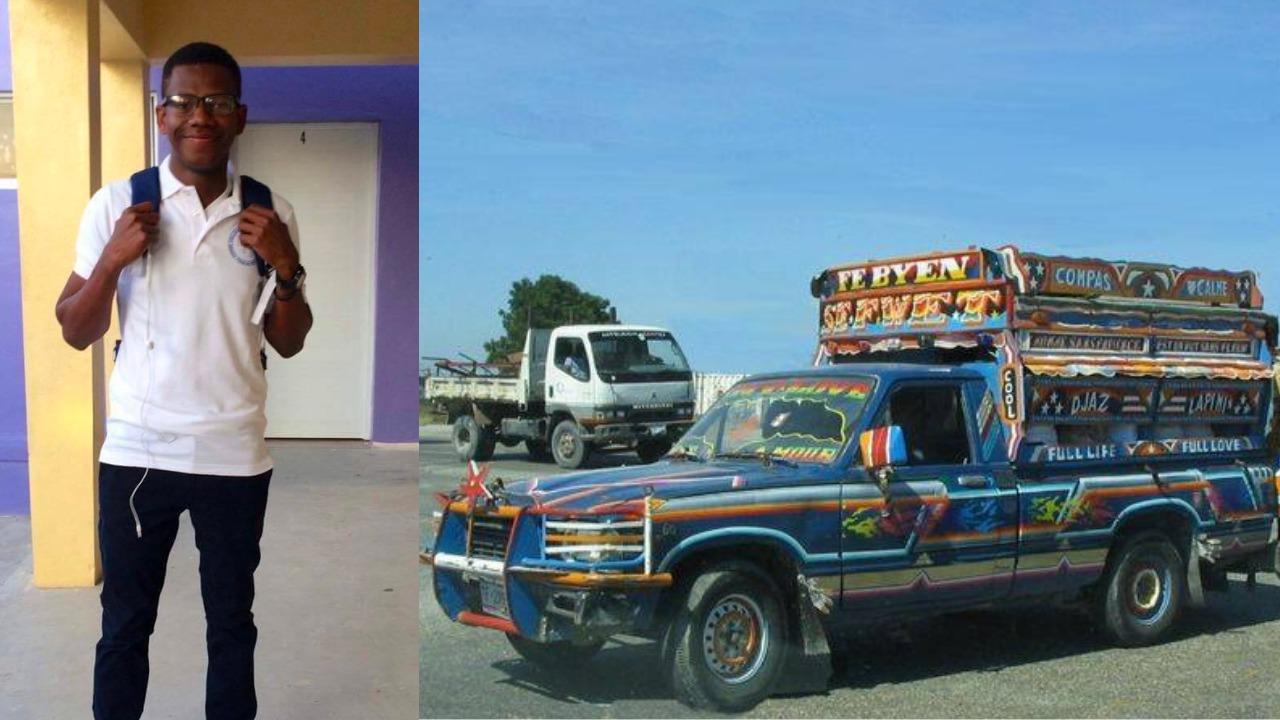

Manno’s first day of high school in 2017. He had to take two tap taps to get there. Tap taps are small, privately-owned buses or pick up trucks that serve as shared taxis, and the closest thing you can get to public transportation. |

Year after year, we noticed Manno’s grades were excellent. No matter what the hardship — the heat, the protests, the school’s erratic openings and closings — his academics remained top shelf. As he rounded through adolescence, the idea of college became realistic. Not just a Haitian college. Why not an American one?

Manno took the TOEFL test. He passed his very first try. He filled out an application to Madonna University in Livonia, Michigan and wrote an essay about his life in Haiti, the struggles he overcame, the desire he had to come back and make his country better.

Left: a cake to celebrate Manno’s TOEFL score in March 2018; right: his high school graduation in June of the same year. |

He was accepted and even awarded a scholarship. Some might think that, given his background, Manno was lucky to be attending Madonna.

But I knew it was the other way around.

The road to commencement

The first day we brought Manno to campus, the people there greeted us with a huge rolling storage unit. They figured Manno would have many possessions, given how far he had come, and he’d need help transporting the crates to his room.

But everything Manno owned fit into a gym bag. So he put that gym bag in the giant basket, and we rolled up to his dorm.

Manno (left) and Siem (right) at orientation / new student welcome to Madonna University in the fall of 2018. |

His room was standard issue: tile floor, two beds, a window in between. But when Manno saw the plain, wooden desk, he put his hands on it and his eyes lit up.

“I get my own desk?” he marveled.

When we told him yes, tears formed in his eyes. I have never seen a young man more grateful for anything.

He took that attitude into every class he attended. Every lecture he attended. He was serious about his studies. Serious about his assignments. And while he’d never had regular access to a computer before, he navigated life in the digital environment, and now knows how to do things that leave me dazed.

We visited with Manno throughout his four years, and since the school is close, he stayed at our house on weekends and on long school breaks. At night we’d invite him to watch TV or go someplace with us, but more often than not, he’d decline because “I have to study.”

Not surprisingly, his grades were exemplary. I would ask how he did at the end of each semester and he’d reply in his gentle voice, “I think I did OK.”

Then I’d get an email that read 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0.

Manno majored in psychology and has decided he wants to be a pediatrician, because “in my country, there is a great need for doctors to help children.” Medical school is his next stop, and he’s already preparing for the MCAT and getting applications together.

But first came the matter of his college graduation. And there we were Saturday as he reached the stage, my wife, myself, four of his Haitian “brothers” from the orphanage, his biological brother, and more than a dozen friends and admirers.

And when he started across the stage, I felt a chill zap from my arms to my head, and I tried to hold the camera steady. Then I heard these words:

“Emmanuel Gedeon, bachelor of science, with highest honors.”

And I welled up.

And meanwhile down in Haiti, all of Manno’s orphanage brothers and sisters were gathered around a TV set watching a stream of the event, and when they saw him, they exploded with glee, a joyful noise that I swear I could hear all the way up in Michigan.

They call it “commencement” because it kickstarts a new stage of life. But the stage that had just finished for Manno — for all of us — was the thing we wanted to celebrate Saturday. Only one percent of Haitians ever go to college. Less than half of those attend college in the U.S.

Manno, a boy without a desk, a boy without parents, a gentle, studious boy raised in a crowded concrete orphanage shared with 50 kids on a third of an acre, had become a man with a college degree of the highest order.

There must be a sentence that aptly describes that accomplishment, but I can’t come up with it. I can only recall what my mother used to say when I did something that made her and my Dad proud. I never understood it. I just thought it was her quirky way of talking.

She’d say, “Our cup runneth over.”

Now I know what she meant.

Your donation supports scholars like Manno!

|

A recurring gift brings more resources to the bilingual school at Have Faith Haiti, for young scholars like Manno and Knox.

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments