I sometimes get asked what’s the best moment in running the orphanage.

That’s easy.

Arriving.

We have a tradition of overdoing it when someone shows up. Big time. It started years ago, and it goes on to this day.

“When we get a visitor, WHAT DO WE DO?” I will holler.

“RUN AND HUG THEM!” the kids will holler back.

And that’s what happens. Arrivals are a messy loving chaos. Understand that you can’t just sneak into our orphanage. We have a big thick gate, and a security guard who is on the inside, so in order to let him know you are there you have to do some big-time honking. Especially if he is elsewhere on the grounds. Or in the bathroom.

Honk! Honk! You can be out there hitting the horn for two minutes. So there’s no way your arrival is a surprise. Heads turn. Everyone looks to the gate. Finally, your vehicle bounces in — we have the world’s worst driveway, thanks to the Haitian street repair crews; many a chassis has been bruised, dented or ripped while entering — and then you pull up to an area under the trees, close to the gazebo where the kids are usually playing.

By that point curiosity has taken over, and dozens are children are drawing near to the vehicle like yellowjackets swarming to a discarded candy bar. And once the door opens? Well, that’s it. The running begins. The leaping. The squealing. The piling on. The hug upon hug upon hug.

It’s the best feeling in the world, isn’t it? To be greeted in love?

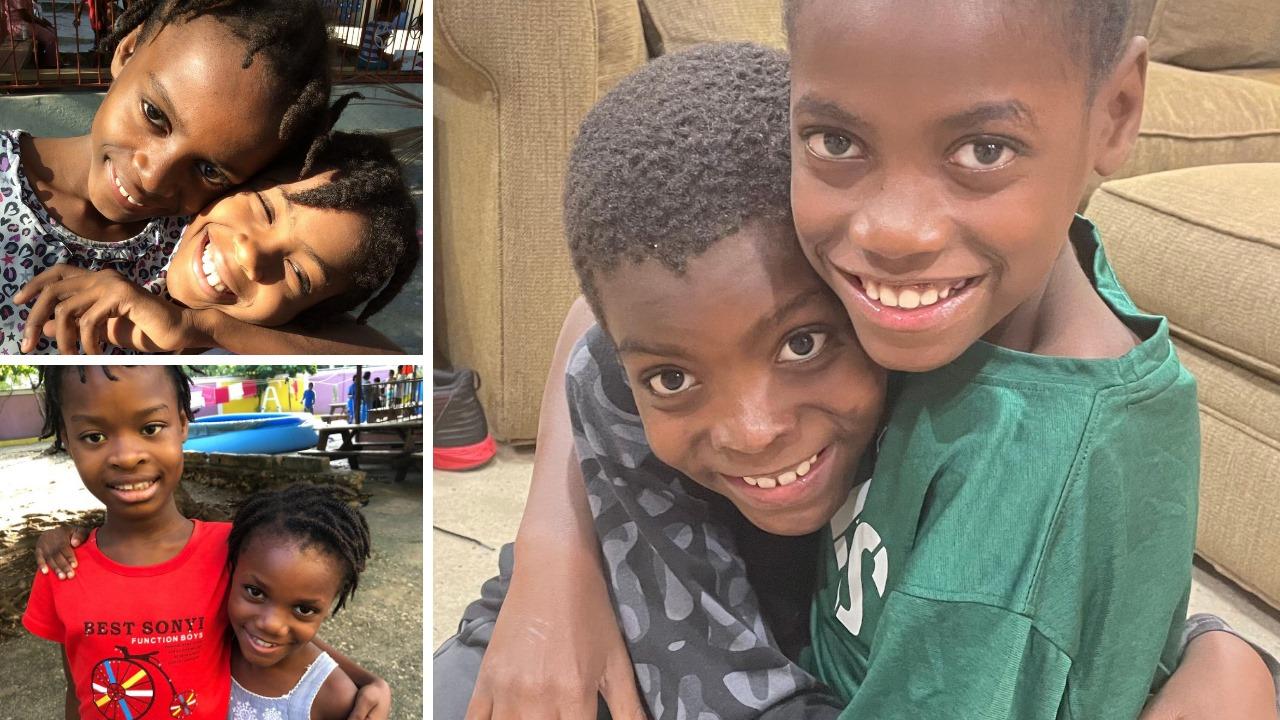

Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

The creole word for hug is “anbrase” — like embrace — and we say it all the time. When our kids gather around a new nanny, we tell them “anbrase li” (hug her) and they do. When a volunteer first arrives, same thing. “Anbrase li.” It’s gotten so common that the kids do it by themselves.

The arrival hugs are the most enthusiastic, and often come with questions whispered in my ear.

“Did you bring us a movie, Mr. Mitch?”

“Are you staying for my birthday, Mr. Mitch?”

Certain kids are particularly proud of their embraceability. Moise, for example, only 8 years old, will climb up my body with no help, and hang on by his legs in a vice-like grip around my torso.

Dorvinsky, 11, a smallish boy whose smile occupies at least 40 percent of his face, fancies himself a mini-chiropractor, and likes to squeeze around my tailbone until I grunt (I swear he has actually adjusted a few vertebrae.)

The teenage girls lean in gently, the teenage boys try some heavy arm-around-the-shoulder shaking. But everybody gets into it. No one stays on the sidelines.

Maybe this is my doing. I am forever telling them “You’re never too old for a hug.” And many of the kids who started doing this by leaping into my arms are now are taller than me, and stronger as well.

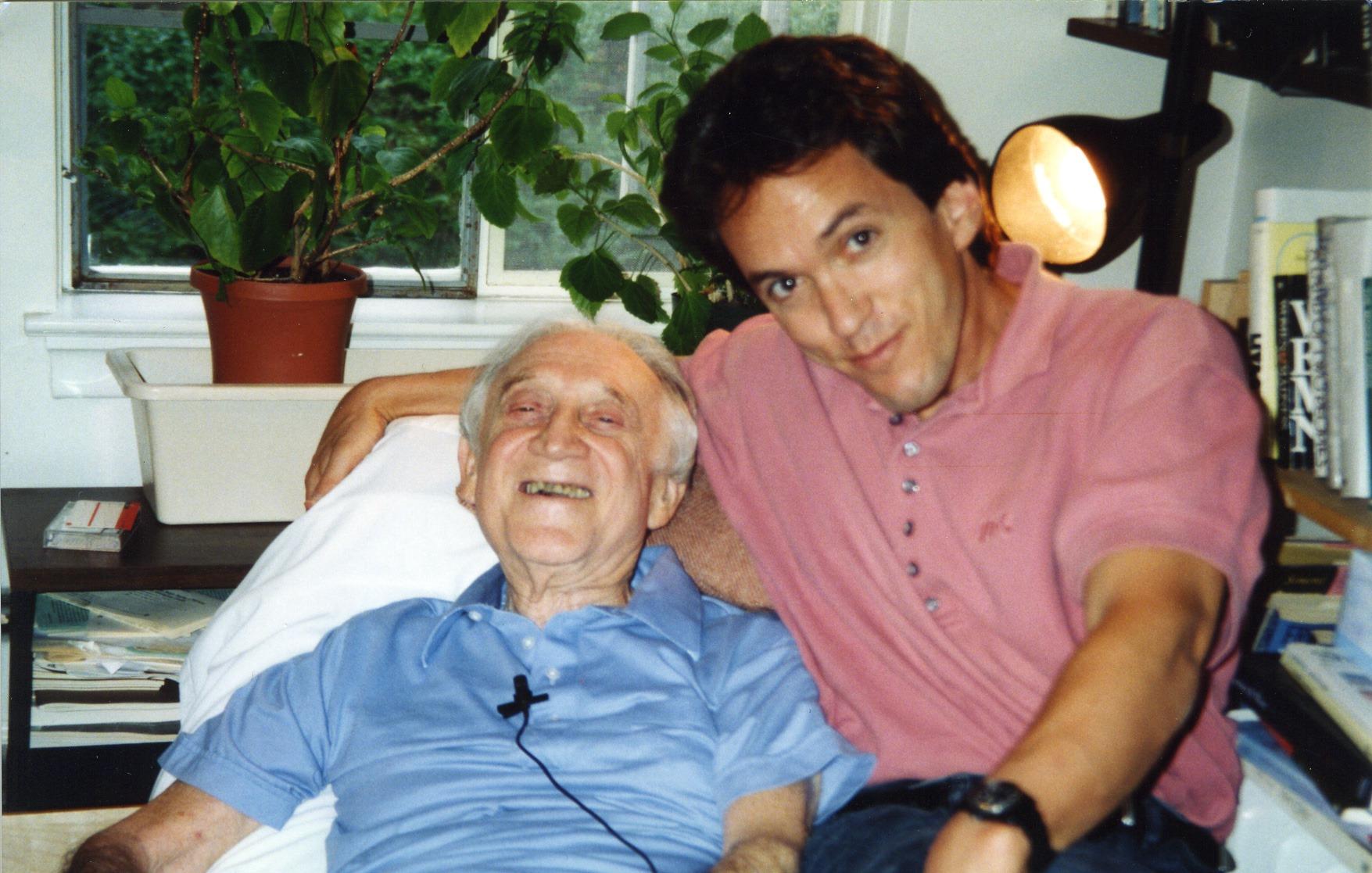

But I learned from my beloved college professor Morrie Schwartz (the Morrie of “Tuesdays with Morrie”), who was always seeking a hug. He taught me, as he was dying from ALS, that we desperately need human touch when we’re leaving the world, same as when we enter the world as newborns.

“That makes sense to me,” he said. “It’s symmetrical. What doesn’t make sense is why, in between the coming and the going, we act like we don’t need that physical touch.”

He’s right.

Especially here in Haiti.

Morrie Schwartz, left / Photo credit: Rob Schwartz |

We recently had a couple of the teenage kids come back to America with us for medical reasons. They stayed for a couple of weeks, even after the doctor appointments were finished. We had regular routines, making breakfast together, riding bicycles together, and of course, big hugs in the morning, and big hugs before bed at night.

When they left, they wrote my wife and me thank you notes that they left on our kitchen table. They were precious. In one of them, Bianka, a 15 year-old teenage girl, wrote “These two weeks are the safest I have ever felt in my life.”

I teared up when I read that. It reminded me how much we take our safety, our security, our very right to live for granted here. In Haiti, where danger lies outside every gate, where kidnappings, shootings or sudden violent demonstrations are commonplace, and where there always seems to be an earthquake or hurricane that is coming or just happened, security is precious. Feeling safe is a luxury.

Maybe this is why the orphanage’s culture of hugging is as strong as it is. We are not in a great neighborhood. We do not have access to reliable public services. We are not wholly safe. But when you come through our gates, you are part of us, part of a family that revels in itself, in its joy, in its recognition that in numbers, we are stronger, and in caring, we are more secure.

Photo credit: Danielle Cutillo / Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

Remember that song, “Embraceable You”? Everyone at our place is an Embraceable You. We may be the most hugged corner of Haiti. If so, so be it. As Morrie said, why pretend the feeling we need at the start and end of life isn’t what we need in the middle? I am leaving next week for my monthly stay in Haiti and already I am thinking about the car door swinging open, and the moment that makes it all worthwhile, the best moment of all.

***

JOIN ME LIVE: THURSDAY, OCTOBER 7. 2PM EST. FACEBOOK.

Reports about children’s mental health for the last 18 months are staggering, but providing a sense of safety and security for our children has always been an essential part of Have Faith Haiti. Social and emotional learning and support are built in to the care we offer. I’d love to speak with you about some of the social and emotional issues our children experience in Haiti, when they first arrive in America for school or extended visits, and take your questions about how we do it for a family of 50+! I also invite parents, teachers, and other care workers who work with kids and teens to share some of their advice. Please drop me questions in the comments at the end of the article and I will answer them tomorrow!

Follow me on Facebook to get the alert when I’m live.

***

Cover image photo credit: Danielle Cutillo

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments