Dear friends,

This column was originally published in the Detroit Free Press, and I wanted to be sure you heard about the vital work HERO Client Rescue is doing. They have made it possible for us to get our most critically ill children out of the dangers of Port-au-Prince — the first step in an arduous journey to the U.S. for necessary medical care. It has happened many times. For the safety of our children and staff, we don’t tell you when it happens, but it does. And it will continue to. HERO needs help for their work to continue, as will we in the oncoming months as Haiti’s situation remains dire.

I hope to share important news with you soon. In the meantime, I hope that you will take some time to learn more about these HEROes in the Haitian sky.

Your friend, with gratitude as always,

Mitch

This is a story about saving lives, six seats at a time. That’s the passenger capacity of each Bell 407 helicopter that an organization called HERO Client Rescue flies nearly every day from the terrorized city of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, to distant hospitals and safer villages.

Week after week, month after month, these helicopters — three of them — are now the only way small numbers of people, many serious medical cases, are able to evacuate the capital city, which is overrun by gang violence. In Port-au-Prince, murders, fires, kidnappings — even being hit by stray bullets — are part of everyday life.

“Outside people don’t realize how serious the situation is,” says Stacy Librandi, 44, who created HERO 11 years ago as a ground ambulance and emergency flight company, but has seen it morph into something even more critical. “The city is a war zone. And innocent people living in Haiti, just trying to survive, are left to defend themselves in a country where mostly it’s only the bad guys that have firearms.”

More than 700,000 Haitians have now been displaced by the endless gang violence, as of last October. That’s 700,000 homeless people searching for places to live. Commercial airlines have stopped flying into Port-au-Prince, after gangs shot at airplanes. The roads out of the city are controlled by those gangs as well, as are the ports, so there is no driving or sailing away.

Right now, the only safe movement is via helicopter, and pretty much the only helicopters operating are the ones that HERO bravely puts into the sky up to four times a day. They land on soccer fields, hillsides, hospital lawns. They sell seats to those who can afford them to help pay for passengers who cannot — particularly those in need of medical care. Many of the hospitals in Port-au-Prince are either shuttered, destroyed, or unable to fully operate because doctors and nurses can’t get there.

“The Haitian people are in an utter state of survival,” says Clay Lang, one of HERO’s helicopter pilots. “And it’s hour-to-hour survival.”

Moving experience

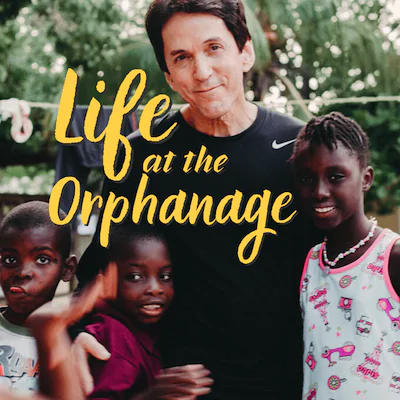

I just returned from another trip to Haiti. I have written about the orphanage I operate there in Port-au-Prince, and the now 70-plus amazing children who have thrived under its care.

A number of those kids require serious medical attention for issues such as cerebral palsy, seizures, malnutrition and brain damage. We used to fly them on commercial airlines out of Port-au-Prince. Now we must use helicopters for a journey to the northern city of Cap-Haïtien, site of the country’s only functioning international airport.

Our children have been strapped into HERO’s seats. So have many others. A 2-year-old baby who needed immediate open-heart surgery. A teenager with head trauma from a motorcycle crash. Cancer patients. Newborns. Adoptees.

“I remember landing in a soccer field and a group of kids approached,” Lang recalls. “One older boy said, ‘Why are you here?’ I told him there was a child with a broken neck we were supposed to transport. He said ‘Oh, yes, I’ll get him.’ The whole village came back carrying the kid. It was so moving.”

Lang is a good example of the kind of people who do HERO’s work. Trained to fly in the Navy, he has a full-time job fighting fires in the western U.S. with a company called Sky Dance helicopters. But his boss, Jason Legge, “gave me paid time off to come to Haiti.” He flew for one excellent service, Haiti Air Ambulance, but when they were forced to pause operations, he shifted over to HERO.

Librandi says there are about 70 employees like Lang working with HERO, many of them medical people. But with the current chaos, it is often not enough.

“In recent months, there have been days where I take hundreds of calls, from 6 a.m. until after midnight,” says Hunter Picken, a HERO executive who has been with the company since 2017. “When I started, I was using my personal cellphone. It didn’t stop.

“People would hear gunshots in their neighborhood and call me late at night saying, ‘I need to get out tomorrow morning.’”

Because of the enormous expense of flying and maintaining helicopters (not to mention getting insurance) HERO has to make tough decisions about who can fly when, and at what price, and how they can fund the countless charitable cases they operate for free when lives or health are at stake.

Picken, 31, even recalls organizing numerous flights on Christmas Day, including an 87-year-old woman who could not walk, and several Haitian kids who were being adopted, but whose adoptive parents could not get to them.

“We often end up picking up children at orphanages, transporting them somewhere, arranging places for them to stay, getting them doctors,” he says. “It’s become much more than just flights.”

More than helicopter rescues

Librandi, who oversees this whole operation, splits her time between Haiti and Traverse City, where she lives with her husband, Aaron Dankers, 49, a retired law enforcement officer and now HERO’s head of security. Like many who embrace Haiti’s children (myself included) Librandi got involved after the tragic 2010 earthquake. She went there ostensibly as a photographer, but spent time working alongside the American military and learning the ropes of disaster relief. She and a few friends eventually rented a truck and began distributing food and water that wasn’t getting to the people.

“I discovered that when you are willing to try different approaches to things, you can be very effective in helping people. That was super interesting to me.”

She found her calling.

In little over a decade, HERO has grown to include trauma centers, ambulances, armored car operations, and even plans to bring and operate a CT machine into a country that desperately needs one.

But currently, the helicopter rescue is dominant, because demand is so great.

“The thing is, we operate out of Pétionville (a section of Port-au-Prince),” Picken explains. “It’s one of the last safe areas. But the gangs are closing in on so many neighborhoods, that we’re left with a very small circle of safety. Some of staff who live outside that circle can’t get to us sometimes because of the gangs in their streets.”

Librandi agrees. If Pétionville should fall, there will be no place for the helicopters to operate. And likely no safe way in and out of a metropolitan area that holds 3 million people.

‘A privilege to fly them’

While HERO is run as a company, it also has a 501(c)(3) charitable foundation (that can be accessed at www.heroclientrescue.com). Donations would help them provide more rescue flights, but they are so busy dealing with the current crisis, Picken says, they don’t have much time to devote to fundraising.

Even so, they deserve support. Without their daily flights, there is next to no movement in or out of Port-au-Prince for old people in distress or children with medical emergencies.

“I remember flying three handicapped children once,” Lang, the pilot, recalls, “and they needed special chairs just to support themselves. And in order to get them to the helicopter, the people in their area created, like, a makeshift wheelbarrow. They cared so much about these children. It’s a privilege to fly them.”

It is a privilege — to be able to help, to be able to make a difference. Can you imagine living in a city where the planes, cars and boats were all locked in by violent gangs, with no way to escape but cramming into a helicopter?

This is everyday life for people in Haiti. HERO tries to give them a lift, literally and figuratively. And as someone who once needed to be airlifted out of Haiti in a chopper, I can attest, when you have no other option, you look at those whirling blades as more than just aviation. You see them as salvation.

And salvation should not be denied to anyone, even if it’s only six seats at a time.

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

It is the season of lent for many Catholic’s . Part of lent is giving alms .plz try churches in your area . This crushes my heart. I gave what I could but as I am blessed I will continue to donate .

Such a wonderful thing it is to be able to help the unfortunate. You are very blessed to be able to do these tasks to help others.

Awed and humbled by these.HERO.team and your dedication.Philip to rescue and.care.for these kids…prayers I can contribute.

Their work is amazing and essential to ours

The story is sad and amazing at the same time. The people who are helping our an inspiration to us all.

Joy and sorrow share the water often

Heartbreaking…while trending news focuses on the world economies and our personal financial portfolios.

Where are the kids being taken to for medical care? Do they typically return to Haiti after the medical care?