Abundance can be confusing. When you are used to so little, a lot can be too much. I had this in mind last week when three of our kids from the Have Faith Haiti orphanage came north with me for medical checkups and therefore were present for an American Thanksgiving.

Bringing our kids to America has always been a delicate process. First, there is enormous paperwork involved. Birth certificates. Passports. Visas. Interviews at the embassy. Permission from the Haitian agency that oversees us. Flight arrangements.

Still, the most challenging part comes when the plane lands. America and Haiti are different enough for adults who can read, watch movies and go online for a glimpse of what lies ahead. But for kids? It’s all unimaginable. From the roar of the jet engines to lifting into the clouds to the people behind the customs counter to the new model vehicle they get into at the airport.

Everything brings stares and hushed reverence. I have noticed our kids are mostly silent during their first few hours in the U.S. Sometimes they whisper to each other and point. But it’s a bit like landing on the moon. You’re almost afraid to speak too loudly, as if you might awaken something you never imagined.

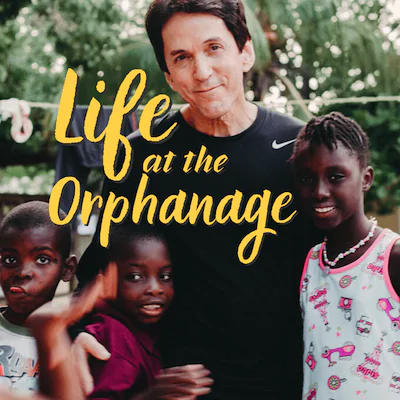

With us now are Knox, 10, Gaelson, 10, and Babu, 13. Knox gets regular therapy treatments for an early childhood brain injury. Gaelson and Babu both had surgeries in America that require periodic checkups.

It’s hard to say what impresses them the most. The smoothness of the roads on the drive from the airport. The massive green signs on the highway. The flashing neon of strip malls and fast food places. All of this is alien to them. All of it draws stares.

And then comes the house. The fact that they get their own beds, no one sleeping above or below them. The kitchen that is right in the middle of things. The television set. Oh Lord. That thing becomes the biggest challenge.

My wife and I often keep a small TV in the kitchen playing a music channel. All that appears is the name of the song, the artist, and a logo. But within minutes I see the kids gaping at that TV, watching the logo float around the background, and I realize the awesome power of a lit screen to a child. And how quickly you have to break that trance if you want to maintain human contact.

And then there’s snow.

Babu decided what to eat on Thanksgiving |

“Can we go outside and play in it?”

That was the immediate request when a blanket of white covered our back yard. Snow is the Holy Grail of strange American experiences for our kids. Obviously, they are never going to see anything like it in Haiti.

But the same goes for the Thanksgiving meal, where the abundance of food is overwhelming. Thanksgiving is a big deal in our home, we host it, and family comes in from all over the country. Consequently, the ovens are packed, the tabletops overflowing, the bowls and trays loaded with delicious edibles.

I remember my early years as a social worker in New York, back in the early 1980s, and how immigrants from Russia had to be accompanied on their first trips to the supermarket because the abundance of available food often left them in tears. It hit them, in the aisles full of snacks and the frozen food freezers, how far they were from home, and how much they’d had to do without while other parts of the world were indulging.

I worry about the same thing with our kids in Thanksgiving. We constantly explain “This isn’t a normal meal” and “Not everyone in America gets to eat this way” and they nod and say they understand, but sometimes I wonder.

Gaelson at breakfast. |

Each morning, when the kids get up, they find me and we go make breakfast together. I ask them to help me, so they see food is something you must prepare, not simply order. They quickly jump in, cracking eggs, toasting bread, pouring milk over cereal. We pray before every meal. They say “thank you” for everything and help us clean the dishes.

But you can make all the rules you want. The eyes don’t lie. And what our three young ones see is consumption and possession on a scale that is unimaginable for them in Haiti.

Clockwise from top left: Babu and her American “cousin” Mia; Mitch and Knox watch “Lilo and Stitch”; Knowx with a new faux furry friend. |

It is a fine line we walk, keeping that in perspective. I am heartened by the fact that, of all the activities that are offered — from a trip to the frozen yogurt store, a visit to a zoo, a drive to a trampoline place or even the snowman making in the yard — the thing they get most excited about is calling back to the kids in Haiti.

We hold up the iPhone and, through garbled transmission, they squeal and wave at the kids back home and ask what they are doing and, almost remarkably, “What are you eating?”

I can only imagine how faraway the children here seem to the ones back at the orphanage, as if they were calling from the moon. It feels like a moon visit sometimes. We navigate the craters as best we can, even mindful of how blessed we are in the country, and how to spread those blessings without overwhelming the large-eyed children who briefly share this strange new world alongside us.

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments