PORT-AU-PRINCE — This is a post about the outside and the inside of our orphanage, and how in Haiti there is a world of difference between the two.

The inside, I have written about. A slightly ramshackle, third of an acre rectangle with five small buildings painted banana yellow and lavender; a chapel, a trio of connected classrooms, a dorm, a music room, and a guest house. There’s a gazebo where we pray and meet, and a massive green kenep tree that hangs over our “soccer” field, which is really just a potholed grassless area with old tree roots poking up like oatmeal lumps.

The inside is also 50-plus children (we just took in nine new ones this month) who wake us up each morning with squealing and laughing and singing.

The inside is a guard at the gate, which only opens for returning or exiting cars.

The inside is safety, familiarity, a place where a teenage boy named Edney, who is about to go off to college in America, runs laps in a square wanting to stay in shape for his big trip. He passes three kids reading books on a stoop, a small group learning a card trick around a table, and a handful of teenaged girls on the steps outside the kitchen, laughing at a private joke.

The inside, in our orphanage, is the known world.

The outside is something else.

That outside came barreling over our walls last week, first in the form of a text message I received from a cherished Haitian friend whose family has been in this county close to 200 years.

It arrived with a ping at 5:30 am.

“The president of Haiti has just been assassinated. Do not go out. Cancel all visits.”

|

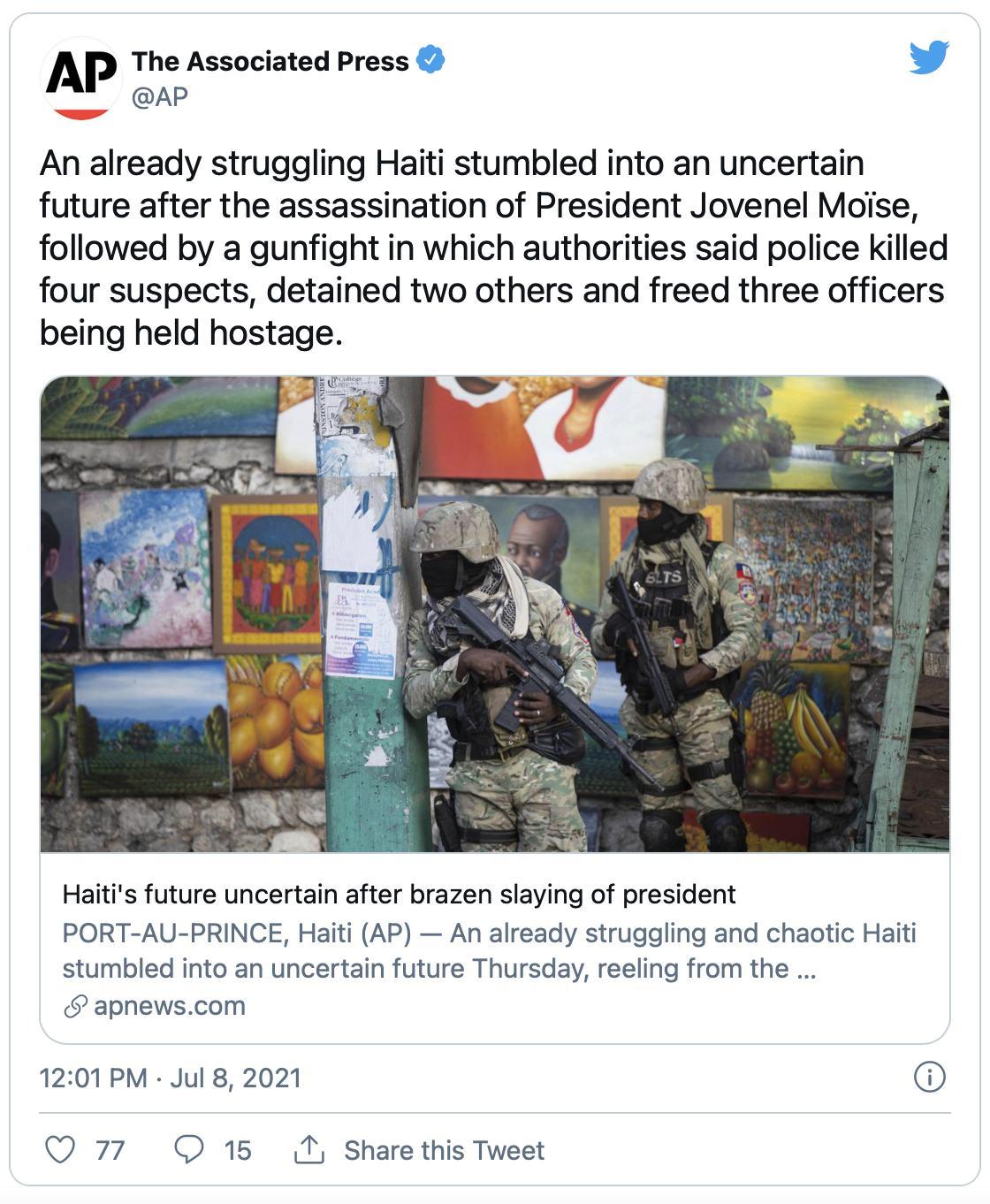

By now, you have probably heard some of the story. Like many things in Haiti, it is confusing, violent, rumor-filled and tragic.

The president of the country, Jovenel Moïse, was murdered in his home in the wee hours of Wednesday morning. A large group of commando style killers reportedly entered his property, somehow didn’t harm a single guard – or even a dog – but managed to put more than a dozen bullets into Moïse’s body, and gouge his eye out. They also shot Moïse’s wife, who was later airlifted to an American hospital.

Theories flew. They are still flying. Columbian mercenaries are part of the story, and many have been arrested, but no one is sure if they were hired to kill, capture or protect the president. Political rivals have denied involvement but are, of course, suspect. Questions are everywhere. Meanwhile, the line of succession was thrown into the hopper when the next in line, the president of the Supreme Court, recently died of COVID-19, and the next in line, the prime minister, was just ousted by Moïse in favor of a new one. But the new one could not be confirmed by the parliament – because there is no parliament! It’s been disbanded.

There are currently less than a dozen people running the government in Haiti.

Less than a dozen?

Against this backdrop, the president being assassinated in his own home leaves the average Haitian wondering the same two things: if the president isn’t safe, how can we be safe? And if the president is dead, what happens to us?

Here is what happened to us. We lost our electricity. It would not come back for days. We took stock of our water (good) our food (OK) and our fuel (not so good.) We were warned to beef up security immediately and we managed, through friends, to hire, that afternoon, two plainclothes police officers to roam our grounds and climb atop our buildings to scour the streets.

Orphanages have been attacked, most recently in April in Croix-des-Bouquets, where bandits killed a guard and raped several teenaged girls. With the outside portending chaos after Moïses’ murder, we spent the day going over panic plans, how to set off alarms, scream a safety word, and get the children to the roof of our tallest structure to try and fend off any attack.

|

What’s strange – maybe even ironic, an overused word in Haiti – was that the day before, the outside had been a blessing.

For the first time in nearly two years (thanks to COVID-19) we took a field trip to the beach. This involved two buses, 50 kids, 16 staff members, a police escort and two hours in traffic. Didn’t matter. Upon arrival, our kids went nuts.

The place we went to, Wahoo Bay Beach Club, had a pool as well as a beach, plus a basketball court and a small restaurant where meals had been arranged. For our kids, it might as well have been heaven. They splashed, dove, threw a beach ball around and never stopped smiling. The little ones wore inflatable wings on their arms and leaned against doting nannies in the shallow water. The teenaged boys showed off their cannonballs.

Archange, 3, enjoys the crystal clear water / Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

Mitch Albom helps Estafania, 11, float in the pool as Cinlove, 15, looks on / Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

At lunch, the entire group welcomed a plate full of Haitian specialties, chicken, beans and rice, plantains, pikliz. They were so thrilled to be outside the walls, and they said “Thank you Mister Mitch” about a million times, although in truth, the trip was planned by our great friend Verena, and we sent her pictures to let her know what a success it was.

In fact, the only time during the eight-hour experience that there was quiet was on the bus rides out and back. On American field trips, this can be when kids make the most noise; they scuffle or poke fun at each other.

But our kids were mostly silent in their seats. That’s because they rarely get a look at the poverty parade that lines the streets of Port-au-Prince. This is the other part of the outside: crowded vendors, one atop the other, trying to sell any meager ware to get enough food to eat. Kids their age banging on car windows trying to sell trinkets or water. Women, old before their time, carrying huge barrels or trays atop their heads. Endless traffic. Choking fumes.

The outside is sobering reality, and our kids stare at it as if watching a world that they’ve heard about, but is usually hidden in the attic.

Courtesy of Have Faith Haiti |

With the death of Moïse, there is no hiding. The nation was stunned by the murder, and for days after the streets were eerily quiet, everything closed, everyone hesitant.

It will not last. A power vacuum in Haiti always means a scramble for control, and whether through elections, force, or martial law – which Haiti is under now – there will be mayhem and fear. The nation braces for it. We brace for it.

|

For one sunny afternoon, the outside was a beautiful panorama of blue water and sand and thatched-roof patios and Coca-Cola bottles. And then it was all gone, in an after-midnight murder of the president, and Haiti was once again leaderless, the outside world reverting to danger, and no walls safe enough to let you sleep without worry.

I spent the next few nights tossing on my pillow, thinking about how fast 50 kids can get to a rooftop, how we need to get someplace safer, how this country can be so glorious and so grim at the same time, and how to steer our children between the two.

|

Click here to watch a previously live broadcast from the orphanage, discussing the latest from Haiti.

Join a community of monthly donors

Join a community of monthly donors

0 Comments